When you hear “digital accessibility,” what’s the first thing you think of?

It's common to think that as long as your desktop website is in great working order then you've done the work. Yet, data from more than 3,000 lawsuits filed in 2020 indicates that is no longer the case. Other types of digital accessibility lawsuits grew in 2020 and continue to gain attention in 2021. Digital accessibility in 2021 is more than having an accessible desktop website.

The disability community is increasingly advocating for accessibility on all types of digital assets, including mobile apps, mobile sites, and videos. The data shows that public-facing brands are expected to have a digital presence that provides reasonable and effective accommodation for all types of users.

To help you uncover areas where you may not be providing equal access for the disability community, this blog will take a look at the three most common types of digital accessibility lawsuits.

What’s in a typical desktop web Accessibility lawsuit?

While not all desktop website ADA lawsuits all follow the same path, many include the following aspects in the claim: One person identified the issue(s) with the website; there’s often a claim with a list of general issues found on the site; this is accompanied by a declaration that key features aren’t available to make the site accessible to a user.

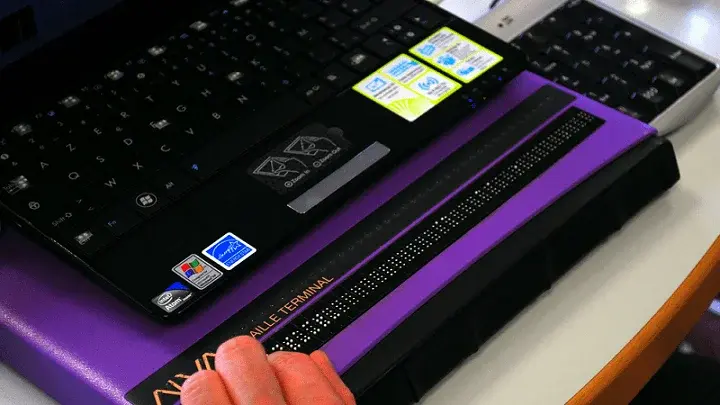

In many cases, a blind plaintiff using a screen reader will find the issue and file the claim. Many lawsuits will cite the desktop operating system and the screen reader used.

In 2020, we found the most common desktop combination cited in lawsuits as “Windows/JAWS.”

Many ADA-related lawsuits will cite the WCAG 2.1 AA as the standard that brands are expected to uphold. The lawsuit below is a good example of a suit filed about a desktop checkout process.

The text on the above image from a digital accessibility lawsuit reads, "In order to proceed with payment, shoppers must select from various payment options, including PayPal, American Express Checkout, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. In the alternative, shoppers must proceed with secure checkout by using another payment card. If shoppers select this option, B&H displays a pop-up window prompting them to login or check out as a guest. Shoppers who perceive visually may answer these various prompts by clicking the appropriate spots on their smartphone's screen. Unfortunately, the Digital platform does not alert screen readers of this pop-up window. Instead, screen readers remain focused on the content of the Digital Platform's underlying page, making the pop-up window invisible to them."

One checkout option displays a pop-up window that prompts users to either login or checkout as a guest. This digital platform’s checkout popup was not registered by screen readers. This lawsuit alleges that blind users are unable to complete the checkout process.

It should be noted that historically and in 2020, website desktop lawsuits make up the majority of digital accessibility lawsuits filed in federal court.

What’s in a typical mobile site or mobile app lawsuit for digital Accessibility?

Blind plaintiffs are most common for mobile ADA lawsuits both for apps and websites, similar to desktop websites.

Some of the claims for apps, however, are a little different than desktop website lawsuits.

App digital accessibility lawsuit claims are more likely to cite the following: Missing alt text; some variation of the app not being compatible with Apple’s VoiceOver screen reader; redundant descriptions; mislabeled elements; and the touch target being too small.

Check out this blog post for an easy, 6-step mobile app accessibility checklist.

Some estimates show that 90 percent of the time spent on mobile devices occurred within native applications, making accessible native app extremely important to user experience. If you are a member of the UX team, download this whitepaper on how WCAG 2.1 match up in mobile and native app design.

Here’s another great example, which claims that links and buttons on the site don’t describe what they do.

Above is an example from a retail website. Text reads, "Links and buttons on the website do not describe their purpose. As a result, blind users cannot determine whether they want to follow a particular link, making navigation an exercise of trial and error. For example, visitors who perceive content visually will recognize the Website's chat icon, and understand that by clicking it, Defendant will redirect them to the Website's chat function. Unfortunately, this icon is not labeled with any descriptive alternative text. As a result, when Plaintiff hovers over it, his screen reader is unable to read the link."

As the text above notes, the chat icon, is readily apparent to users without sight issues, but if it doesn’t have alt text. This means blind users won’t know where to click. Therefore this lawsuit alleges that blind users are therefore unable to navigate the site properly.

As noted above, "touch target being too small" is an area cited in app lawsuits that are not in desktop lawsuits. This has to do with how a blind person navigates via touch on mobile.

You can learn more about the experience of a blind person on a mobile device versus on desktop via our 2020 webinar, "How a blind person uses a website on mobile versus desktop."

What’s in a video Digital Accessibility lawsuit?

Video lawsuits have unique qualities that are different from mobile and desktop site lawsuits.

The user is more likely to be deaf than blind, for example, with a lack of subtitles or closed captions being a common reason listed.

Some lawsuits, however, are also focused on an inability to access video with keyboard commands alone. Others will still cite a lack of audio descriptions that could have enabled blind users to better understand the context.

Below is an example of a video that was flagged by an ADA lawsuit. The videos did not have audio descriptions, which the plaintiff law firm alleges resulted in the video being inaccessible to screen readers, as screen reader users are unable to read the on-screen text in the video itself.

The text explains, "Defendant's Website is so constructed that the videos do not have audio descriptions. The 'Original Weighted Compression Vest' video includes narration and onscreen text, and shows children using the vest, but an audio description is not present. The renders the video inaccessible to screen reader users."

An increasing number of companies are offering webinars in the wake of in-person conferences being canceled. Companies hosting online events should think about audio descriptions on webinars too if those recordings will be repurposed and posted on the website as video.

Upgrade All your digital assets WCAG 2.1 AA

Today, more than 20% of the US population (or more than 60 million people) have permanent disabilities. The disability community is the fastest-growing demographic in the US and worldwide. Getting accessible for all your digital assets just makes good business sense.

Updating to WCAG 2.1 AA will help you to improve accessibility for three major groups of customers: users with cognitive or learning disabilities, users with low vision, and users with disabilities on mobile devices.

Fortunately, all of the mandates from WCAG 2.0 are included in 2.1, so if you were previously up to date, you can build on what you already have to make sure your providing an accessible experience on all your digital assets.

If you're totally new to accessibility, we recommend you get started by running an automated test with UsableNet AQA.

If your team has the technical expertise to remediate accessibility issues but isn’t sure which issues are most urgent, AQA can help your team test, fix, verify, and maintain accessibility at scale. You will find your free results organized into a summary and details. You can toggle between them by using the tabs at the top of the page.

Or if you've already run some automated tests and are ready to take accessibility to the next level, contact us to speak to a member of our accessibility team. Our experts can discuss your accessibility initiatives, the progress you've already made, and how UsableNet might be able to assist you with your goals for the future. Contact us.